A recording of the Royal Opera’s 1957 English-language production of Hector Berlioz’s monumental opera THE TROJANS has come my way and it has many felicitous elements. The translation appropriately relies on Early Modern English pronouns (thee/thou/thine) to evoke the ancient kingdoms of Troy and Carthage. With a few passing cuts in this epic opus, Rafael Kubelik helms the performance impressively and the sound quality is quite good for a recording made 50+ years ago.

For years after I discovered opera in 1959, I subscribed to the British magazine OPERA. The cast of this TROJANS is full of ‘Covent Garden’ names that were familiar to me thru the magazine long before I heard any of their actual voices: people like Amy Shuard, Forbes Robinson, Noreen Berry, Marie Collier, Joan Carlyle, Michael Langdon, and Lauris Elms.

At The Met, Blanche Thebom was an established star (Met debut 1944) by the time she appeared as Dido in London, and Jon Vickers made his role-debut as Aeneas in this ’57 performance, which became a signature part for the great tenor.

Curiously, this is a performance in which each of the three principal singers proves less than ideal, yet the overall performance – thanks to Maestro Kubelik and the strong supporting cast – still makes a vivid impression.

Amy Shuard does not seem absolutely at home in the role of Cassandra; she has passing pitch problems and some of the music seems to lay too low for her to make her finest impression. Her commitment is undoubted, and her sense of the drama and her fine high notes are positive aspects. But often one just wants more power and colour in the lower-middle and lowest ranges of this music, which rather awkwardly straddles the mezzo/soprano divide.

Blanche Thebom as Dido has the right aristocratic feeling for Dido’s music; she becomes more passionate as her love for Aeneas is inflamed – and then thwarted – by destiny. Thebom’s strong top notes stand out, and she fills scene after scene with perfectly good singing; yet her voice sometimes seems matronly and a bit lacking in tonal bloom.

It would be nice to be able to say that Jon Vickers’ first Aeneas was an unalloyed triumph, but despite his excellent diction and superbly individual voice – which amply conveys the the character’s innate humanity and rather grizzled tenderness – and his sense of vocal identification with every aspect of the hero’s personality, he is not at ease in the role’s top-most notes. He omits the highest vocal arc of the love duet, reveals some effort in the demanding “Inutiles Regrets!” and seems rather uncomfortable in his final cry of “Italie!” As Vickers sang the role in the ensuing years, his voice found itself increasingly at home in this demanding music; and indeed even here in 1957 there is much impressive singing.

Despite some reservations about both Thebom and Vickers, they do achieve some especially fine soft harmonies as they sing of the mysterious wonders of love in the great duet “Nuit d’ivresse.”

The stalwart baritone Jess Walters sings strongly as Chorebus; his duet with Ms. Shuard is full of apt dramatic touches from both singers – and the soprano’s concluding top-B is her best note of the performance.

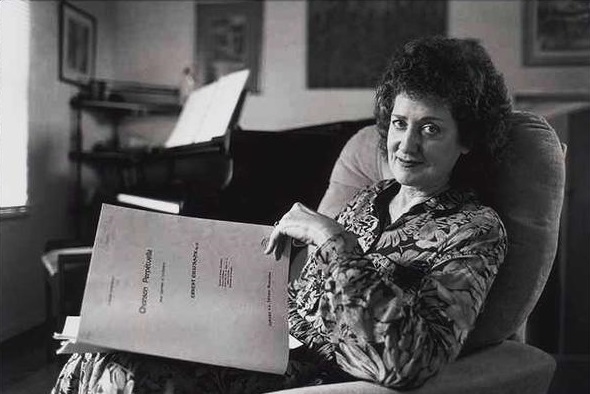

Lauris Elms (above) makes an especially lovely impression as Dido’s sister, Anna. Anna’s role includes two wonderful duets: the first, with Dido, in which she urges her widowed sister to consider opening her heart to another love; and the second, with Dido’s minister Narbal. Narbal’s concerns about the effects of the Dido/Aeneas attachment on Dido’s ability to rule are brushed off by her sister who is so delighted at Dido’s new-found happiness. Ms. Elms has a full-throated lyric mezzo sound and dips into her lower range without over-emphasis; her voice is clear and so is her diction. I keep going back to Anna’s two duets, just to enjoy Ms. Elms’ vocalism.

Joining Lauris Elms in the Anna/Narbal duet, basso David Kelly – who was an indispensable Covent Garden regular for fifteen years – is a perfect match for the mezzo; his diction and well-produced voice make for a very effective portrayal.

I was particularly pleased with the Iopas of Richard Verreau (above); this French-Canadian tenor was my first Faust in a performance at the Old Met in 1963. He sings the high-lying solo “O blonde Cérès” quite beautifully, in a more passionate and extroverted interpretation of the aria than is sometimes heard. In the second of LES TROYENS’ two taxing and exposed solos for lyric tenors, Irishman Dermot Troy sings the plaintive aria of the homesick sailor Hylas with attractive lyricism.

TROYENS is such a unique and treasure-filled opera; whatever concerns this recording raises, I am sure I will return to it time and again.