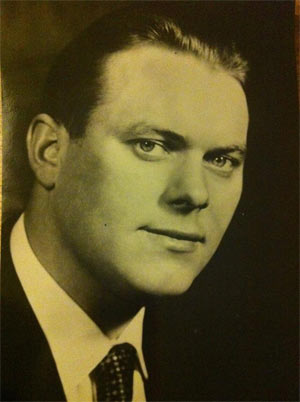

Above: composer Bohuslav Martinů

Sunday January 17th, 2016 matinee – Yet another highly enjoyable concert in the Philharmonic Ensembles series at Merkin Hall: artists from The New York Philharmonic performing chamber music in an intimate setting.

These days, more than ever, I am looking to music to lift my spirits and help alleviate the symptoms of weltschmerz that threaten to overwhelm me. Feeling particularly low this morning, part of me wanted simply to stay home; but I headed down to Merkin and just a few moments into the opening Martinů, the dark pall began to lift. By the end of the concert, I felt fortified and ready to face another week.

MARTINŮ – Duo No. 1 for Violin and Cello, H.157

Joo Young Oh, violin; Alexei Yupanqui Gonzales, cello

The afternoon’s opening work was composed by Bohuslav Martinů in 1927 while he was living in Paris, studying with composer Albert Roussel. It’s a delightful two-movement piece – the first soulful, the second a lively dance. Superbly performed by violinist Joo Young Oh and cellist Alexei Yupanqui Gonzales, the slow movement impelled my rejuvenation process after just a few bars with its heartfelt melodies and lovely meshing of the two voices. In the second movement, a long cello solo was really a joy to hear; I thought the violin might have an equal opportunity, but instead the piece danced on to its ending. The two players had a fine rapport, the violinist reaching over to shift the cellist’s score as the cello ‘cadenza’ was launched.

John SICHEL – Fishbowl Diaries No. 3

Vladimir Tsypin, violin; Blake Hinson, bass; John A. Sichel, narrator

In something of a departure, John Sichel’s Fishbowl Diaries #3 featured a spoken narrative, delivered by the composer himself. The three short vignettes were accompanied by the Philharmonic’s Vladimir Tsypin, violin, and Blake Hinson, bass. The first tale, entitled Heather From Card Member Services, was truly droll and had the audience laughing aloud. Juliet of The Rats, a story of thwarted infatuation in a laboratory setting, had Shakesperian allusions. The third and final setting, Dolphin Man: Mwa-ha-ha-ha-ha, struck close to home: it tells of that moment in childhood when those of us who are ‘different’ realize that people are laughing at us, either gently or cruelly. Mine happened when I was nine or ten years old, and it put a damper on my self-confidence that has stayed with me to this day. It’s kind of amazing that Mr. Sichel has hit this nail so perfectly on the head.

DVOŘÁK – Piano Trio in E minor, Op. 90, Dumky

Anna Rabinova, violin; Patrick Jee, cello; Wei-Yi Yang, piano

Totally engrossing, uplifting, and thought-provoking was the experience of hearing today’s playing of the Dvořák Dumky trio. “Dumka” literally means “thought”, and the word also refers to a type of Slavic folk-song that veers in mood from mournful to euphoric. Each of the six dumka that Dvořák has strung together for us in this imaginative and marvelous work is a feast in and of itself: poignant melodies abound, only to swirl unexpectedly into vigorous dance passages.

The music calls for both deeply emotional colours and exuberant virtuosity. Anna Rabinova’s passionately expressive playing of the violin line found a complimentary spirit in the rich piano textures of Wei-Yi Yang, whilst heart-stoppingly gorgeous tone from cellist Patrick Jee gave the music its soulful core. The three musicians moved me deeply in this fantastic performance. Bravi, bravi, bravi…

BEETHOVEN – Quintet for Piano and Winds

Sherry Sylar, oboe; Pascual Martínez Forteza, clarinet; Kim Laskowski, bassoon; R. Allen Spanjer, horn; Yi-Fang Huang, piano

Still more delights followed the interval with a performance of the Beethoven Quintet for Piano and Winds. Here, Yi-Fang Huang was the lyrically deft pianist, and the wind voices gave us an especially mellow blend in the Andante cantabile. R. Allen Spanger, who I met and enjoyed chatting with often while I was working at Tower (he’s an avid opera fan) produced that autumnally luminous sound that I always strove for in my horn-playing years but never achieved. The three reed players were congenially matched: Sherry Sylar (oboe), Pascual Martinez Fortenza (clarinet), and Kim Laskowski (bassoon) traded melodies and mingled their timbres in a performance rich in sonic rewards.

We emerged from the hall into a gentle snowfall. The music had worked its magic. My sincere gratitude to all the participating artists.