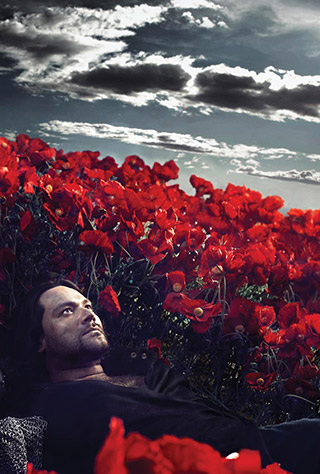

Above: Ildar Abdrazakov as Prince Igor at The Met

Monday February 24th, 2014 – I fell in love with Borodin’s PRINCE IGOR back in the late 1960s when I saw several performances of it in an English-language production at New York City Opera. The staging was traditional and featured unforgettable performances by my beloved Maralin Niska (Yaroslavna) and that great singing-actor William Chapman (doubling as Khan Konchak and Prince Galitsky); much of the music became imbedded in my operatic memory, and the famed Polovtsian Dances were staged as a warriors-and-maidens extravaganza, led by the great Edward Villella who was on-loan from New York City Ballet.

The City Opera’s production used painted drops and built set-pieces to evoke the locales, with era-appropriate costumes. It spoke to us directly of the time and place that Borodin’s music conveys. The Metropolitan Opera’s new production of PRINCE IGOR is more generalized; the women of Putivi are seen in 1940-ish dresses and coats even though the action supposedly takes place in the year 1185.

The evening overall was a rather mixed affair: musically sound and with some interesting visual elements (the field of poppies) it does not really end up making a strong dramatic statement; this may be due in part to the episodic character of the opera itself. In this updated setting we don’t get much of a feel for exoticism. Khan Konchak for example is not seen as an Asiatic warlord with a scimitar but rather as a rather anonymous military type in a toxic-yellow uniform.

The opening scene takes place not in a public square in Igor’s capital but rather in a great hall where the Prince’s troops assemble in preparation for going to war. This is fine, but it rather short-circuits the effect of the solar eclipse that is taken as a bad omen by the populace. Despite this warning, Prince Igor leads his troops out to fight the Khan; he is defeated and captured.

Black-and-white films of the Prince and of his soldiers are shown during interludes; these are rather superfluous though it’s nice to see two men in a gentle embrace as they await the coming battle. The field of poppies is really very attractive and the ballet – with the dancers is gauzy cream-coloured costumes – is sensuous and flowing rather than militant and grand. I loved spotting several of my dancer-friends: Loni Landon, Michael Wright, Anthony Bocconi, Kentaro Kikuchi, Matt Van, and Bradley Shelver.

In this production, the three scenes of Act II all take place in the same spacious great hall as the prologue; nevertheless, there are longish pauses between scenes.

The first intermission stretched out unduly and the far-from-full house seemed bored waiting for the opera to resume. There were very short rounds of applause after the arias, which were for the most part attractively sung. A huge double explosion as the Act II curtain fell with Putivi under attack almost made me jump out of my seat.

Gianandrea Noseda conducted with the right sense of grandeur, but also with a nice feeling for the more reflective moments. Perhaps what was missing was a Scheherazade/mystique in the Polovtsian scene. Noseda sometimes tended to overwhelm his singers; and the very open sets did not help to project the voices into the hall. The orchestra and chorus were on optimum form.

In the title-role, Ildar Abdrazakov sang beautifully, especially in his great aria of anguish over his defeat and of his longing for his beloved Yaroslavna far away. The role, often sung by baritones, seemed to work well for Abdrazakov even though his voice is more basso-oriented. Read about Mr. Abdrazakov’s recently-issued CD of Russian arias Power Players, here. Igor’s lament is a highlight of this excellent disc.

Stefan Kocan and Mikhail Petrenko appeared as Khan Konchak and Prince Galitsky respectively and both sang well though neither seemed as prolific of volume as I have sometimes heard them. Sergei Semishkur’s handsome tenor voice and long-floated head-tone at the end of his serenade made his Vladimir a great asset to the evening musically, though he was rather wooden onstage. The veteran basso Vladimir Ognovenko was a characterful Skula, with Andrey Popov as his sidekick Yeroshka.

Oksana Dyka’s stunning high-C as she bade farewell to Igor in the prologue sailed impressively into the house; but later, in her Act I aria, the voice seemed unsteady and lacking in the dynamic control that made Maralin Niska’s rendering so memorable. Niska always took a flaming, sustained top note at the end of the great scene with the boyars where the palace is attacked. Dyka wisely didn’t try for it. The sultry timbre of Anita Rachvelishvili made a lush impression in the contralto-based music of Konchakovna, and it was very nice to see Barbara Dever onstage again in the brief role of Yaroslavna’s nurse: I still recall her vivid Amneris and Ulrica from several seasons ago.

A particularly pleasing interlude came in the aria with female chorus of the Polovtsian Maiden which opens the scene at Khan Konchak’s camp. Singing from the pit, the soprano Kiri Deonarine (above) showed a voice of limpid clarity which fell so sweetly on the ear that one could have gone on listening to many more verses than Borodin provided. It was a definite vocal highlight of the evening, and also showed Mr. Noseda – and the Met’s harpist – at their senstive best.

Metropolitan Opera House

February 24, 2014

PRINCE IGOR

Alexander Borodin

Prince Igor.............Ildar Abdrazakov

Yaroslavna..............Oksana Dyka

Vladimir................Sergey Semishkur

Prince Galitzky.........Mikhail Petrenko

Khan Konchak............Stefan Kocán

Konchakovna.............Anita Rachvelishvili

Skula...................Vladimir Ognovenko

Yeroshka................Andrey Popov

Ovlur...................Mikhail Vekua

Nurse...................Barbara Dever

Maiden..................Kiri Deonarine

Conductor...............GIanandrea Noseda